This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Male Breast Cancer

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from breast cancer (men only) in the United States in 2024:[1]

- New cases: 2,790.

- Deaths: 530.

Male breast cancer is rare.[2] Fewer than 1% of all breast carcinomas occur in men.[3,4] The mean age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years; however, men of all ages can be affected by the disease.

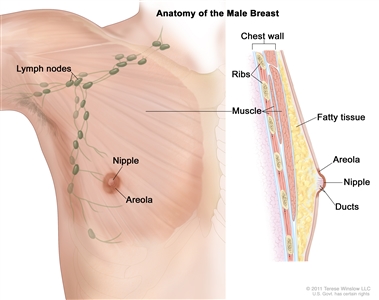

Anatomy

Anatomy of the male breast. The nipple and areola are shown on the outside of the breast. The lymph nodes, fatty tissue, ducts, and other parts of the inside of the breast are also shown.

Risk Factors

Predisposing risk factors for male breast cancer appear to include:[5,6]

- Radiation exposure to breast/chest.

- Estrogen use.

- Diseases associated with hyperestrogenism, such as cirrhosis or Klinefelter syndrome.

- Family health history: Definite familial tendencies are evident, with an increased incidence seen in men who have a number of female relatives with breast cancer.

- Major inheritance susceptibility: An increased risk of male breast cancer has been reported in families with BRCA mutations, although the risks appear to be higher with inherited BRCA2 mutations than with BRCA1 mutations.[7,8] At age 70 years, men have an estimated cumulative risk of breast cancer of 1.2% if they are BRCA1 mutation carriers and 6.8% if they are BRCA2 mutation carriers.[9] Genes other than BRCA may also be involved in predisposition to male breast cancer, including mutations in the PTEN tumor suppressor gene, TP53 mutations (Li-Fraumeni syndrome), PALB2 mutations, and mismatch repair mutations associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome).[10,11,12] For more information, see the sections on High-Penetrance Breast and/or Gynecologic Cancer Susceptibility Genes in Genetics of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers, and Male Breast Cancer Screening and Surveillance for BRCA1/2 Carriers in BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risks and Management.

Clinical Features

Most breast cancers in men present with a retroareolar mass. Other signs include:

- Nipple retraction.

- Bleeding from the nipple.

- Skin ulceration.

- Peau d'orange.

- Palpable axillary adenopathy.

Because of delays in diagnosis, breast cancer in men is more likely to present at an advanced stage.[2,5,13]

Diagnostic Evaluation

Breast imaging should be performed when breast cancer is suspected. The American College of Radiology recommends ultrasonography as the first imaging modality in men younger than 25 years because breast cancer is highly unlikely. Mammography is performed if ultrasonography findings are suspicious.

For men aged 25 years or older, or those who have a highly concerning physical examination, mammography is recommended as the initial test and ultrasonography is useful if mammography is inconclusive or suspicious.[14] Suspicious findings should be confirmed with a core biopsy. If the presence of tumor is confirmed, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor type 2 (HER2) expression/amplification should be evaluated.[15]

For more information, see the Diagnosis section in Breast Cancer Treatment.

Histopathologic Classification

Infiltrating ductal cancer is the most common tumor type of breast cancer in men, while invasive lobular carcinoma is very rare.[16] Breast cancer in men is almost always hormone receptor positive. In a male breast cancer series, 99% of the tumors were estrogen receptor positive, 82% were progesterone receptor positive, 9% were HER2 positive, and 0.3% were triple negative.[16]

Prognosis and Predictive Factors

Tumor size, lymph node involvement, and grade are anatomical prognostic factors, while estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status are predictive of response to therapy.

A more advanced stage at diagnosis confers a worse prognosis for men with breast cancer.[2,5,13] A study found that mortality after breast cancer diagnosis was higher in male patients than in female patients. This disparity appeared to persist after accounting for clinical characteristics, treatment factors, and access to care, suggesting that biological factors and treatment efficacy may play a role.[17]

References:

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2024. American Cancer Society, 2024. Available online. Last accessed June 21, 2024.

- Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, et al.: Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer 101 (1): 51-7, 2004.

- Borgen PI, Wong GY, Vlamis V, et al.: Current management of male breast cancer. A review of 104 cases. Ann Surg 215 (5): 451-7; discussion 457-9, 1992.

- Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN: Male breast cancer. Lancet 367 (9510): 595-604, 2006.

- Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN: Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med 137 (8): 678-87, 2002.

- Hultborn R, Hanson C, Köpf I, et al.: Prevalence of Klinefelter's syndrome in male breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res 17 (6D): 4293-7, 1997 Nov-Dec.

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al.: Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature 378 (6559): 789-92, 1995 Dec 21-28.

- Thorlacius S, Tryggvadottir L, Olafsdottir GH, et al.: Linkage to BRCA2 region in hereditary male breast cancer. Lancet 346 (8974): 544-5, 1995.

- Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, et al.: Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 99 (23): 1811-4, 2007.

- Ding YC, Steele L, Kuan CJ, et al.: Mutations in BRCA2 and PALB2 in male breast cancer cases from the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126 (3): 771-8, 2011.

- Silvestri V, Rizzolo P, Zanna I, et al.: PALB2 mutations in male breast cancer: a population-based study in Central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 122 (1): 299-301, 2010.

- Boyd J, Rhei E, Federici MG, et al.: Male breast cancer in the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Breast Cancer Res Treat 53 (1): 87-91, 1999.

- Ravandi-Kashani F, Hayes TG: Male breast cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Cancer 34 (9): 1341-7, 1998.

- Mainiero MB, Lourenco AP, Barke LD, et al.: ACR Appropriateness Criteria Evaluation of the Symptomatic Male Breast. J Am Coll Radiol 12 (7): 678-82, 2015.

- Giordano SH: A review of the diagnosis and management of male breast cancer. Oncologist 10 (7): 471-9, 2005.

- Cardoso F, Paluch-Shimon S, Senkus E, et al.: 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol 31 (12): 1623-1649, 2020.

- Wang F, Shu X, Meszoely I, et al.: Overall Mortality After Diagnosis of Breast Cancer in Men vs Women. JAMA Oncol 5 (11): 1589-1596, 2019.

Stage Information for Male Breast Cancer

Staging for male breast cancer is identical to staging for female breast cancer. For more information, see the TNM Definitions section in Breast Cancer Treatment.

Treatment Option Overview for Male Breast Cancer

The approach to the treatment of men with breast cancer is similar to that for women. Because male breast cancer is rare, there is a lack of randomized data to support specific treatment modalities. Treatment options for men with breast cancer are described in Table 1.

| Stage (TNM Definitions) | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; GnRH = gonadotropin-releasing hormone. | |

| Early/localized/operable male breast cancer | Surgery with or without radiation therapy |

| Adjuvant therapy | |

| Locally advanced male breast cancer | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| Surgical excision | |

| Radiation therapy and endocrine therapy | |

| Metastatic male breast cancer | Aromatase inhibitor therapy in conjunction with a GnRH agonist |

Treatment of Early / Localized / Operable Male Breast Cancer

As in women, treatment options for men with early-stage breast cancer include:

- Surgery with or without radiation therapy (locoregional therapy).

- Adjuvant therapy (systemic therapy).

- Chemotherapy.

- Endocrine therapy.

- Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–directed therapy.

Surgery With or Without Radiation Therapy

Primary treatment is a mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection.[1,2,3] Responses in men are generally similar to those seen in women with breast cancer.[2] Breast conservation surgery with lumpectomy and radiation therapy has also been used and can be offered if standard criteria for breast conservation therapy are met. Results in men have been similar to those seen in women with breast cancer.[4]

For more information, see the Surgical Treatment for Breast Cancer section in Breast Cancer Treatment.

Adjuvant Therapy

The optimal systemic treatment in men with breast cancer has not been studied in randomized clinical trials. Adjuvant therapy should be administered according to the same criteria used for women. Adjuvant therapies used to treat early/localized/operable male breast cancer are outlined in Table 2. For more information, see the Systemic Therapy for Stages I, II, and III Breast Cancer section in Breast Cancer Treatment.

| Type of Adjuvant Therapy | Agents Used |

|---|---|

| HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; LHRH = luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. | |

| Chemotherapy | Docetaxel and cyclophosphamide |

| Doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide with or without paclitaxel | |

| Endocrine therapy | Tamoxifen[5] |

| Aromatase inhibitors with LHRH agonist[5,6,7,8,9] | |

| HER2-directed therapy | Trastuzumab[1,5] |

| Pertuzumab | |

Tamoxifen

Evidence (tamoxifen):

- A retrospective analysis of 257 men with stage I to stage III breast cancer included 50 men who were treated with an aromatase inhibitor (AI) and 207 men who were treated with tamoxifen.[10]

- With a median follow-up of 42 months, treatment with an AI was associated with a higher risk of death compared with tamoxifen (32% with AI vs. 18% with tamoxifen; hazard ratio, 1.55; 95% confidence interval, 1.13–2.13).

In men with contraindications for tamoxifen, single-agent AI therapy is not recommended. AIs should be combined with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues.[6]

In male breast cancer patients, tamoxifen use is associated with a high rate of treatment-limiting symptoms such as hot flashes and impotence.[11]

The German Breast Group conducted a randomized phase II clinical trial (NCT01638247) of tamoxifen with or without a GnRH analogue versus AI plus a GnRH analogue in men with early-stage, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer. Results of this trial are pending.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Borgen PI, Wong GY, Vlamis V, et al.: Current management of male breast cancer. A review of 104 cases. Ann Surg 215 (5): 451-7; discussion 457-9, 1992.

- Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN: Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med 137 (8): 678-87, 2002.

- Kinne DW: Management of male breast cancer. Oncology (Huntingt) 5 (3): 45-7; discussion 47-8, 1991.

- Golshan M, Rusby J, Dominguez F, et al.: Breast conservation for male breast carcinoma. Breast 16 (6): 653-6, 2007.

- Giordano SH: A review of the diagnosis and management of male breast cancer. Oncologist 10 (7): 471-9, 2005.

- Giordano SH, Hortobagyi GN: Leuprolide acetate plus aromatase inhibition for male breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24 (21): e42-3, 2006.

- Cocconi G, Bisagni G, Ceci G, et al.: Low-dose aminoglutethimide with and without hydrocortisone replacement as a first-line endocrine treatment in advanced breast cancer: a prospective randomized trial of the Italian Oncology Group for Clinical Research. J Clin Oncol 10 (6): 984-9, 1992.

- Gale KE, Andersen JW, Tormey DC, et al.: Hormonal treatment for metastatic breast cancer. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase III trial comparing aminoglutethimide to tamoxifen. Cancer 73 (2): 354-61, 1994.

- Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Koutoulidis V, et al.: Aromatase inhibitors with or without gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in metastatic male breast cancer: a case series. Br J Cancer 108 (11): 2259-63, 2013.

- Eggemann H, Ignatov A, Smith BJ, et al.: Adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen compared to aromatase inhibitors for 257 male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137 (2): 465-70, 2013.

- Anelli TF, Anelli A, Tran KN, et al.: Tamoxifen administration is associated with a high rate of treatment-limiting symptoms in male breast cancer patients. Cancer 74 (1): 74-7, 1994.

Treatment of Locally Advanced Male Breast Cancer

Treatment options for men with locally advanced breast cancer include:[1]

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Surgical excision.

- Radiation therapy and endocrine therapy.

The decisions regarding the order and choice of treatments in men are guided by the same principles used for the treatment of breast cancer in women (in particular, evaluation of pathological response).[1,2]

For more information, see the Treatment of Locoregional Recurrent Breast Cancer section in Breast Cancer Treatment.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN: Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med 137 (8): 678-87, 2002.

- Kamila C, Jenny B, Per H, et al.: How to treat male breast cancer. Breast 16 (Suppl 2): S147-54, 2007.

Treatment of Metastatic Male Breast Cancer

Treatment options for men with metastatic breast cancer include:

- Aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy in conjunction with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist.

The management of metastatic hormone receptor–positive male breast cancer relies on the same treatment options used in women. However, data regarding the activity of AIs with GnRH agonists and fulvestrant in men are limited to case series.[1,2,3,4] The administration of an AI in conjunction with a GnRH agonist is recommended on the basis of the adjuvant data. There are no data comparing the activity of fulvestrant alone with fulvestrant in combination with a GnRH agonist.

Based on real world data and limited studies, it is reasonable to extrapolate the use of additional treatment options for men. These treatment options include cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, used in combination with endocrine therapy.

The use of chemotherapy, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in men with metastatic breast cancer is guided by similar treatment principles as in women.[5,6]

For more information, see the Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancer section in Breast Cancer Treatment.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Di Lauro L, Vici P, Barba M, et al.: Antiandrogen therapy in metastatic male breast cancer: results from an updated analysis in an expanded case series. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148 (1): 73-80, 2014.

- Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Chrysikos D, et al.: Fulvestrant and male breast cancer: a pooled analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 149 (1): 269-75, 2015.

- Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Koutoulidis V, et al.: Aromatase inhibitors with or without gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in metastatic male breast cancer: a case series. Br J Cancer 108 (11): 2259-63, 2013.

- Di Lauro L, Vici P, Del Medico P, et al.: Letrozole combined with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for metastatic male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 141 (1): 119-23, 2013.

- Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN: Breast cancer in men. Ann Intern Med 137 (8): 678-87, 2002.

- Kamila C, Jenny B, Per H, et al.: How to treat male breast cancer. Breast 16 (Suppl 2): S147-54, 2007.

Latest Updates to This Summary (12 / 04 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Editorial changes were made to this summary.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of male breast cancer. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Male Breast Cancer Treatment are:

- Fumiko Chino, MD (MD Anderson Cancer Center)

- Tarek Hijal, MD (McGill University Health Centre)

- Joseph L. Pater, MD (NCIC-Clinical Trials Group)

- Carol Tweed, MD (Maryland Oncology Hematology)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Male Breast Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/hp/male-breast-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389234]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2024-12-04